When Passion Transforms into Vengeance

A massive temple bell crashes down, and beneath it writhes a serpentine form – a woman transformed by unrequited love into a vengeful dragon. This is the climactic scene of Dōjōji, one of the most renowned plays in the Japanese Noh theater tradition, where supernatural transformation becomes a metaphor for the destructive power of obsessive attachment.

Quick Facts

- First performed: Late 14th century

- Playwright: Attributed to Kan’ami (1333-1384)

- Runtime: Approximately 120 minutes

- Structure: Two acts (jo-ha-kyū structure)

- Category: Fourth category play (kyōran mono – “madwoman play”)

- Notable adaptations: Kabuki version “Musume Dōjōji” (1753), bunraku puppet theater version

Just want to read the play?

Traditional Japanese Theater: An Anthology of Plays

A collection of noh, kabuki and bunraku plays – including Dojoji.

Japanese No Dramas

A collection of key plays from the Noh tradition, edited and translated by Royall Tyler.

The Noh Theatre of Japan: 15 classic plays

Edited and translated by Japanese culture scholar, Ernest Fenollosa and poet Ezra Pound.

Free version? Try this PDF of Donald Keen’s translation from UCUrvine’s online repository: http://faculty.humanities.uci.edu/sbklein/articles/Dojoji_E1.pdf

Historical Context

Dōjōji emerged during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), when Noh theater was being refined into its classical form under Kan’ami and his son Zeami. The play draws from an earlier Buddhist setsuwa (cautionary tale) found in the Dainihonkoku Hokekyō Genki, compiled in 1040-1044. This was a time when Buddhism’s influence on Japanese culture was at its height, and the play reflects complex attitudes toward women, desire, and spiritual enlightenment.

The setting, Dōjōji Temple in present-day Wakayama Prefecture, remains an important Buddhist temple today. The original tale was likely used by Buddhist priests to illustrate the dangers of worldly attachment and the particular spiritual obstacles faced by women in Buddhist practice.

Plot Overview

A temple is preparing to consecrate a new bell. A mysterious shirabyōshi (female dancer) arrives and requests to perform a dance to celebrate the occasion. Despite the priests’ initial reluctance, they allow her to dance. As her dance grows increasingly frenzied, she reveals herself as the spirit of a woman who once transformed into a serpent out of passionate love for a priest. She leaps into the air and coils around the bell, which crashes down as she transforms into her dragon form.

The second act reveals the full story: years ago, a young priest had stayed at her father’s house while on pilgrimage. The woman fell in love with him, but he fled to Dōjōji Temple. She pursued him so relentlessly that he hid under the temple bell. In her rage and grief, she transformed into a serpent and coiled around the bell, heating it until both the bell and the priest melted. Now her spirit returns, still trapped in the cycle of attachment and vengeance.

Themes & Analysis

Transformation Through Passion

The play’s central metaphor – the transformation from woman to serpent – represents the Buddhist concept of bonno (worldly desires) that bind beings to the cycle of suffering. The serpent transformation specifically draws on Japanese folk beliefs about women’s capacity for jealous transformation, a theme that appears in many Japanese tales.

Sacred vs. Profane

The tension between religious devotion and worldly passion runs throughout the play. The temple setting, with its new bell (symbolizing Buddhist law), contrasts sharply with the dancer’s secular art and eventually destructive passion.

Gender and Power

The play reflects complex medieval Japanese attitudes toward women, particularly their relationship to Buddhist practice. The protagonist’s transformation highlights both female power and its potentially destructive nature when unconstrained by social and religious structures.

Revolutionary Elements

Dōjōji is revolutionary in its sophisticated use of multiple theatrical elements:

- Complex dance sequences that mirror the protagonist’s psychological state

- Innovative use of the mask change (namen) technique

- Integration of multiple literary and religious traditions

- Sophisticated musical structure that builds to the climactic transformation

Cultural Impact

The play has influenced Japanese art for centuries:

- Became a standard piece in both Noh and Kabuki repertoires

- Inspired countless visual artworks, including ukiyo-e prints

- Referenced in modern literature and film

- Continues to resonate with themes of forbidden love and transformation

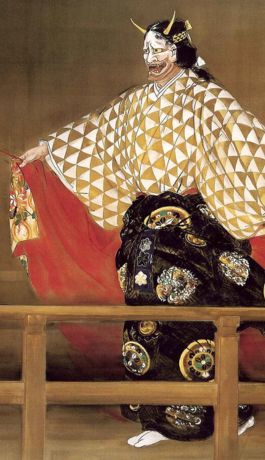

Staging & Performance

Dōjōji presents unique challenges:

- The lead actor must convey both refined grace and supernatural terror

- The bell prop must be both practical and dramatic

- The transformation scene requires precise timing and coordination

- The musical accompaniment must build tension effectively

Reading Guide

Best Translations

- Royall Tyler’s “Japanese Nō Dramas” provides excellent context

- Karen Brazell’s translation emphasizes performance elements

- Donald Keene’s version offers detailed literary analysis

Reading Tips

- Familiarize yourself with basic Noh conventions

- Pay attention to the subtle shifts in the protagonist’s behavior

- Note the symbolic significance of the bell

- Consider how the play would be experienced in performance

Contemporary Relevance

Despite its medieval origins, Dōjōji explores timeless themes:

- The thin line between love and obsession

- Institutional power versus individual passion

- Gender roles and restrictions

- The cost of unchecked emotion

Fun Facts & Trivia

- The temple bell prop weighs approximately 200 pounds

- The mask used for the transformation scene is considered one of the most difficult to perform with

- The actual Dōjōji Temple still exists and houses a famous bell

- The play inspired an entire genre of “bell stories” in Japanese literature

Conclusion

Dōjōji stands as a masterpiece of world theater, combining spectacular staging with profound psychological insight. Its exploration of transformation – both spiritual and physical – speaks to fundamental human experiences of love, obsession, and redemption. For modern readers, it offers a window into medieval Japanese culture while raising questions about desire and its consequences that remain relevant today.

Additional Resources

- “Traditional Japanese Theater” by Karen Brazell

- “Noh Drama and The Tale of Genji” by Janet Goff

- Dōjōji Temple’s historical archives

- Video recordings of performances by notable Noh schools

Whether you’re a student of theater history, Japanese culture, or human nature itself, Dōjōji offers rich rewards. Its tale of transformation, both terrible and beautiful, continues to captivate audiences and readers after more than six centuries.