The Ultimate Medieval Journey of Self-Discovery

Death comes calling, and a man must account for his life. This simple premise launches one of the most profound explorations of morality and human nature in theatrical history. The medieval morality play “Everyman” continues to captivate audiences and readers with its stark examination of life’s final moments and what truly matters when all is stripped away.

Quick Facts

- First performed: c. 1500

- Original author: Unknown (possibly Dutch origin)

- Runtime: Approximately 90 minutes

- Structure: One act, allegorical morality play

- Language: Middle English (multiple modern translations available)

- Notable adaptations: Carol Ann Duffy’s 2015 adaptation at the National Theatre, “Everyone” by Branden Jacobs-Jenkins (2017)

Just want to read the play?

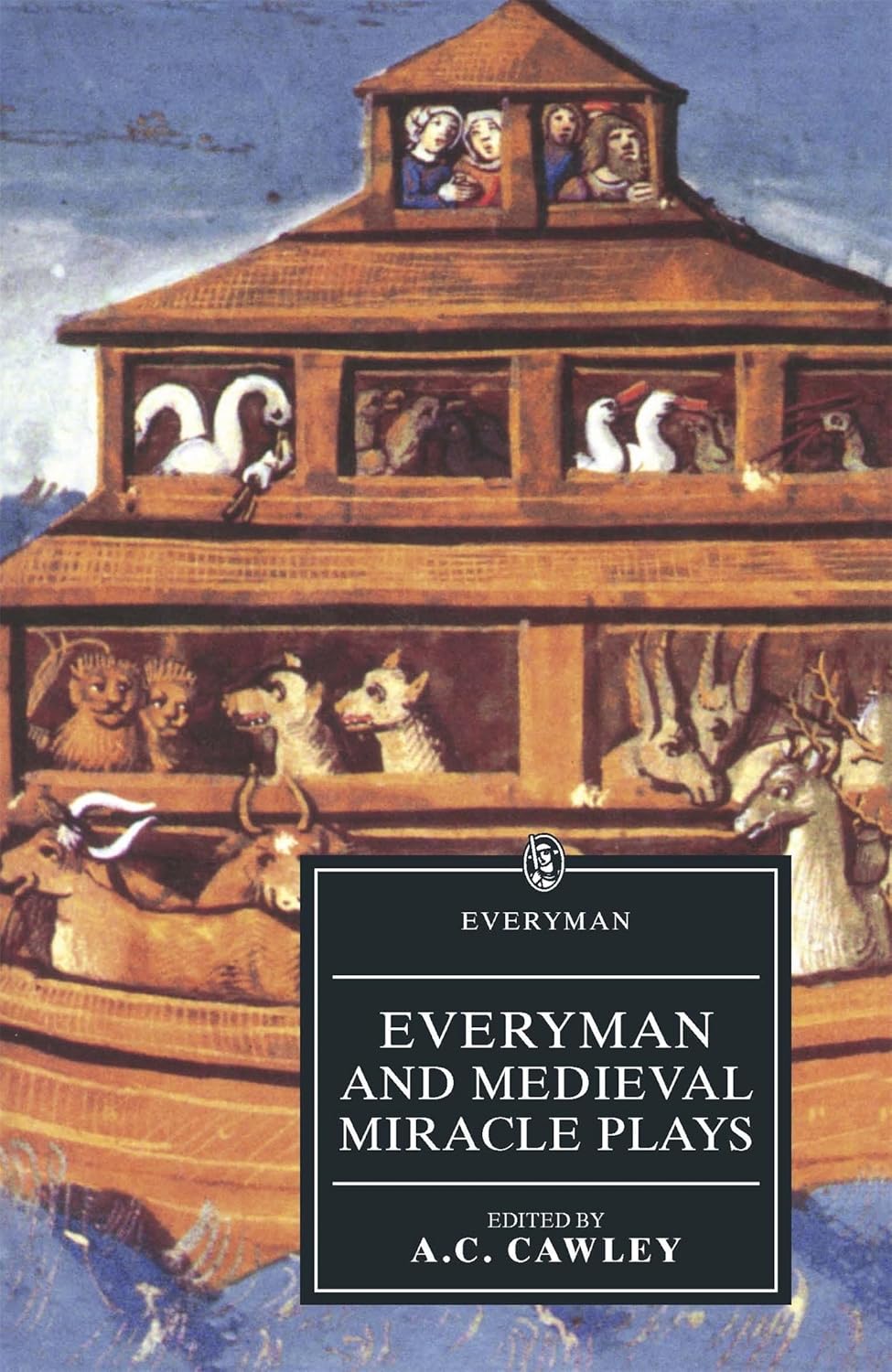

A.C. Crawley edited version

The most comprehensive edition, includes an introduction and extensive notes.

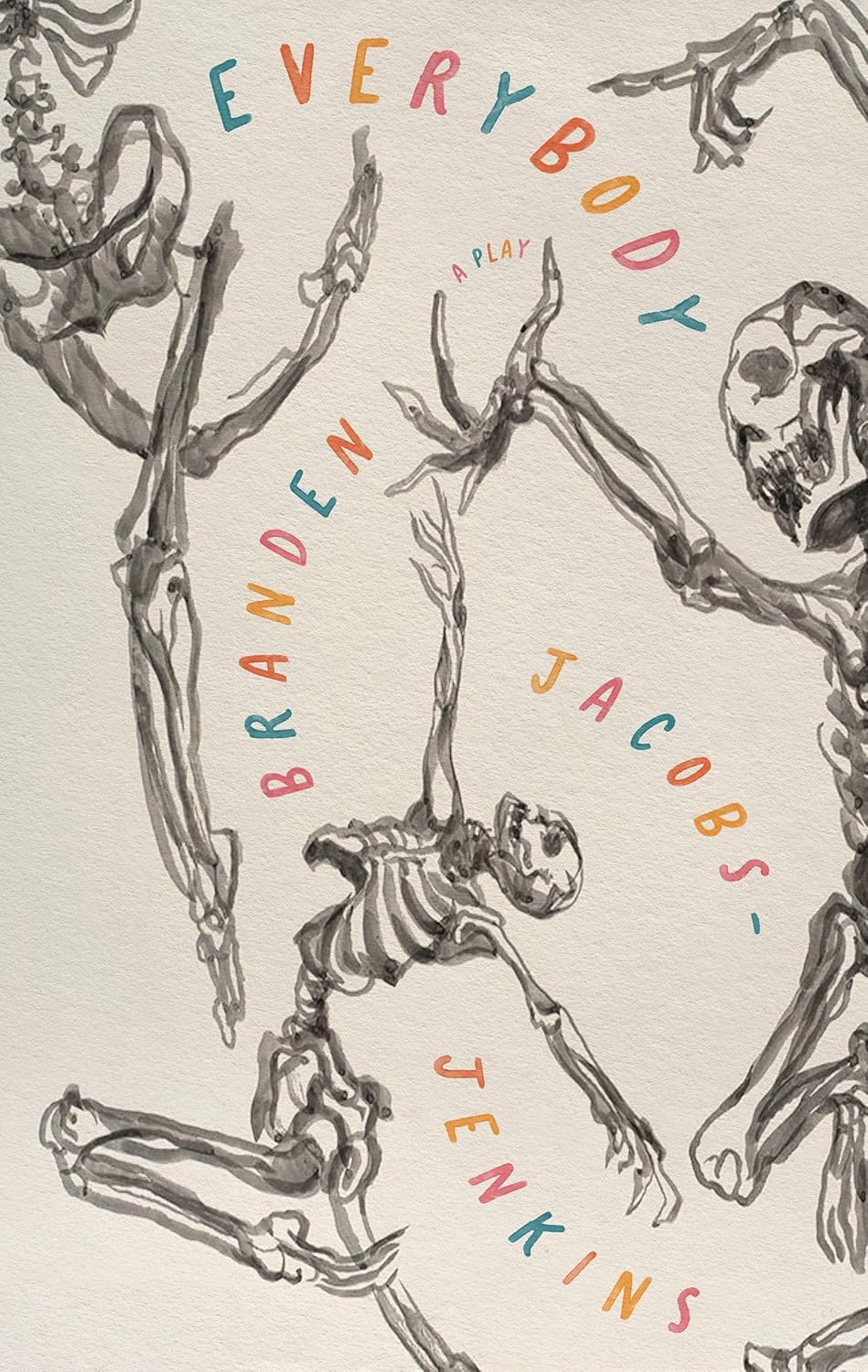

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ “Everybody”

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ re-imagining of Everyman, takes you down a road toward life’s greatest mystery to confront the inevitable.

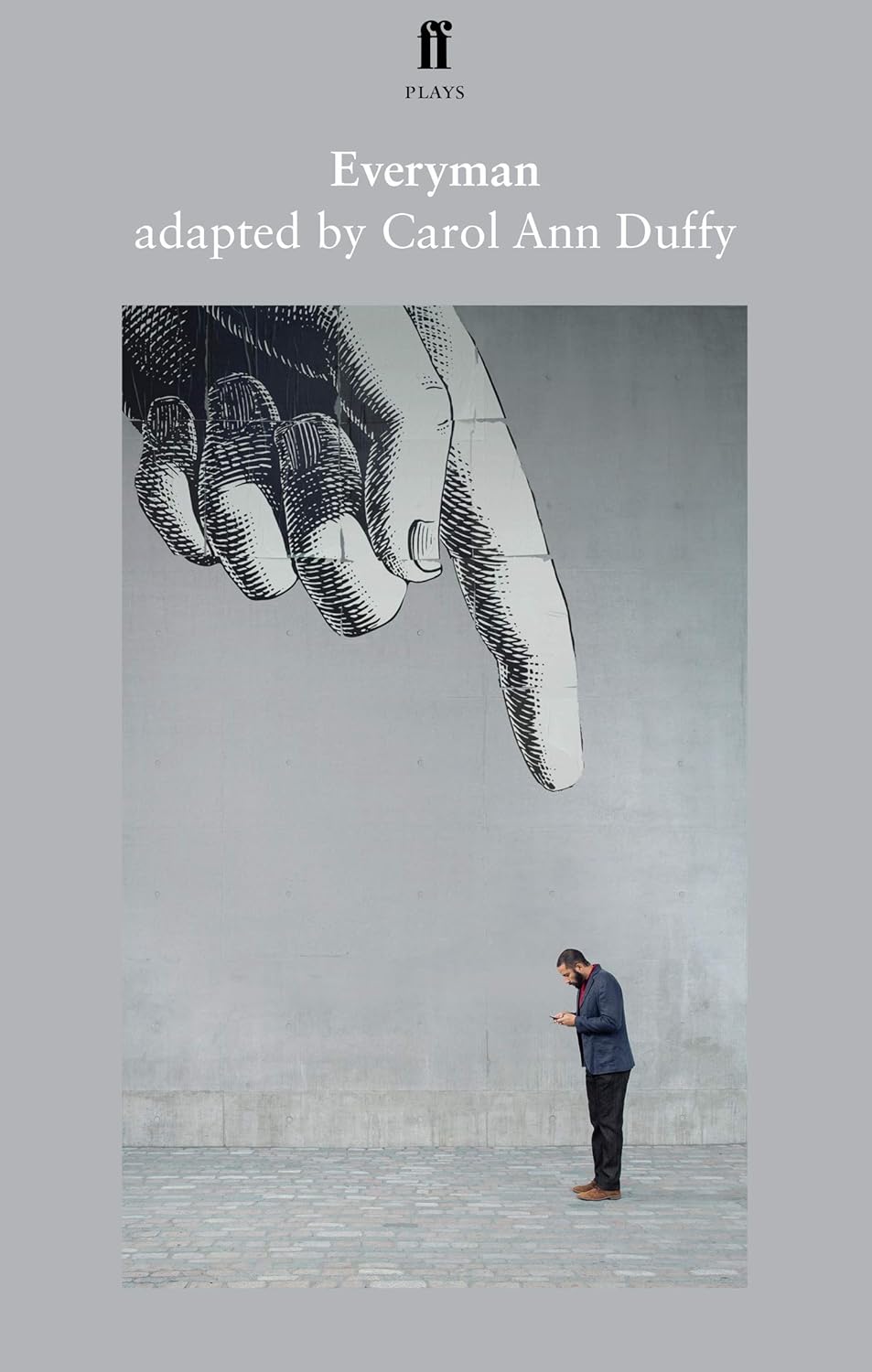

Carol Ann Duffy adaptation

This new adaptation by Poet Laureate Carol Ann Duffy was presented at the National Theatre, London, in April 2015.

Free version? Try the version on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/19481/19481-h/19481-h.htm

Historical Context

Written at the turn of the 16th century, “Everyman” emerged during a fascinating period of transition between the medieval and Renaissance worlds. The Black Death had decimated Europe’s population, the printing press was revolutionizing communication, and the Church’s authority was about to face its greatest challenge with the Protestant Reformation.

The play reflects medieval Christianity’s worldview while incorporating elements of emerging Renaissance humanism. Its focus on individual moral responsibility rather than purely collective salvation marks it as a bridge between these two epochs. The anonymous playwright created a work that transcended its didactic religious origins to become a universal meditation on mortality.

Plot Overview

God, concerned about humanity’s increasing materialism and moral decay, sends Death to summon Everyman for a final reckoning. Everyman, faced with this unexpected journey, desperately seeks companions. He turns first to Fellowship (friends), then to Kindred and Cousin (family), Goods (wealth), and Knowledge. Each abandons him except Good Deeds, who is too weak to accompany him due to his neglect.

Through the guidance of Knowledge, Everyman encounters Confession, leading to the strengthening of Good Deeds through penance. Finally accompanied by Good Deeds, Strength, Beauty, Discretion, and Five-Wits, Everyman approaches his grave. One by one, these companions desert him until only Good Deeds remains to speak for him before God.

Themes & Analysis

The Nature of Existence

The play’s genius lies in its allegorical simplicity that masks profound philosophical complexity. Every character represents an aspect of human life or moral attribute, creating a map of medieval understanding of existence itself.

Mortality and Materialism

The play’s central conflict between spiritual and material values resonates perhaps even more strongly today than in medieval times. Everyman’s initial reliance on material wealth (Goods) serves as a sharp critique of materialism that feels startlingly modern.

Friendship and Loyalty

The abandonment of Everyman by his friends and family creates some of theater’s most poignant moments, forcing audiences to consider the transient nature of worldly relationships.

Revolutionary Elements

While “Everyman” follows medieval dramatic conventions, it revolutionized theater through:

- Its focus on individual moral responsibility

- The sophisticated use of allegory as dramatic device

- The integration of comic elements within serious theological discourse

- Its unique dramatic structure that mirrors life’s journey

Cultural Impact

“Everyman” has influenced countless works, from medieval times to present day. Its basic plot structure (protagonist faced with death seeks meaning) appears in works as diverse as Dickens’ “A Christmas Carol” to Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal.”

Staging & Performance

Modern productions face interesting challenges:

- How to make medieval allegory accessible to contemporary audiences

- Whether to maintain period setting or modernize

- How to physically represent abstract concepts

- Balancing religious elements with universal themes

Reading Guide

Best Translations/Adaptations

- A.C. Cawley’s scholarly edition (most accurate to original)

- Carol Ann Duffy’s modern adaptation (most accessible)

- Branden Jacobs-Jenkins’ “Everybody” (contemporary reimagining)

Reading Tips

- Start with a modern English translation unless specifically studying Middle English

- Pay attention to the progression of who abandons Everyman

- Note the humor amidst the serious themes

- Consider how each character’s name reflects their function

Contemporary Relevance

“Everyman” speaks powerfully to modern audiences through its exploration of:

- The pursuit of material success vs. spiritual fulfillment

- The nature of true friendship

- Questions of mortality and legacy

- The relationship between individual and society

Discussion Questions

- How do modern notions of “good deeds” differ from medieval ones?

- What would your own “goods” say if personified today?

- How does the play’s view of death compare to contemporary attitudes?

- What modern characters would you add to an updated version?

Fun Facts & Trivia

- The play likely derived from the Dutch “Elckerlijc”

- It was performed by traveling players on pageant wagons

- Medieval audiences would have recognized over 100 biblical references

- The role of Death was often played by the lead actor in medieval productions

Conclusion

“Everyman” endures because it addresses the most fundamental human experience: confronting our own mortality. Its genius lies in making the medieval specific universal, speaking across centuries about what truly matters when death comes calling. In our age of material excess and spiritual questioning, its message resonates with particular power.

Additional Resources

- “Medieval Drama: An Anthology” ed. Greg Walker

- “The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Theatre”

- The Folger Shakespeare Library’s digital collection

- British Library’s medieval literature archives

Whether you’re a theater enthusiast, a student of medieval literature, or simply someone grappling with life’s big questions, “Everyman” offers profound insights wrapped in accessible allegory. Its place in our “100 Plays to Read Before You Die” is secured not just by its historical significance, but by its continued ability to make us question what truly matters in our own lives.