The Play About Nothing That Changed Everything

Two men wait by a tree. Nothing happens. Twice. With these deceptively simple elements, Samuel Beckett created what many consider the most important play of the 20th century. “Waiting for Godot” transformed theatrical storytelling and captured the existential anxiety of the post-war world – all while making audiences laugh at the absurdity of existence itself.

Quick Facts

- First performed: January 5, 1953, at the Théâtre de Babylone, Paris

- Original title: “En attendant Godot” (French version)

- Runtime: Approximately 2 hours

- Structure: Two acts, deliberately mirroring each other

- Awards: Multiple, including the 1957 Obie Award for Best Foreign Play

- Notable productions: The 1955 London premiere directed by Peter Hall, the 2009 Broadway revival with Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen, the 2010 Cort Theatre production with Bill Irwin and Nathan Lane

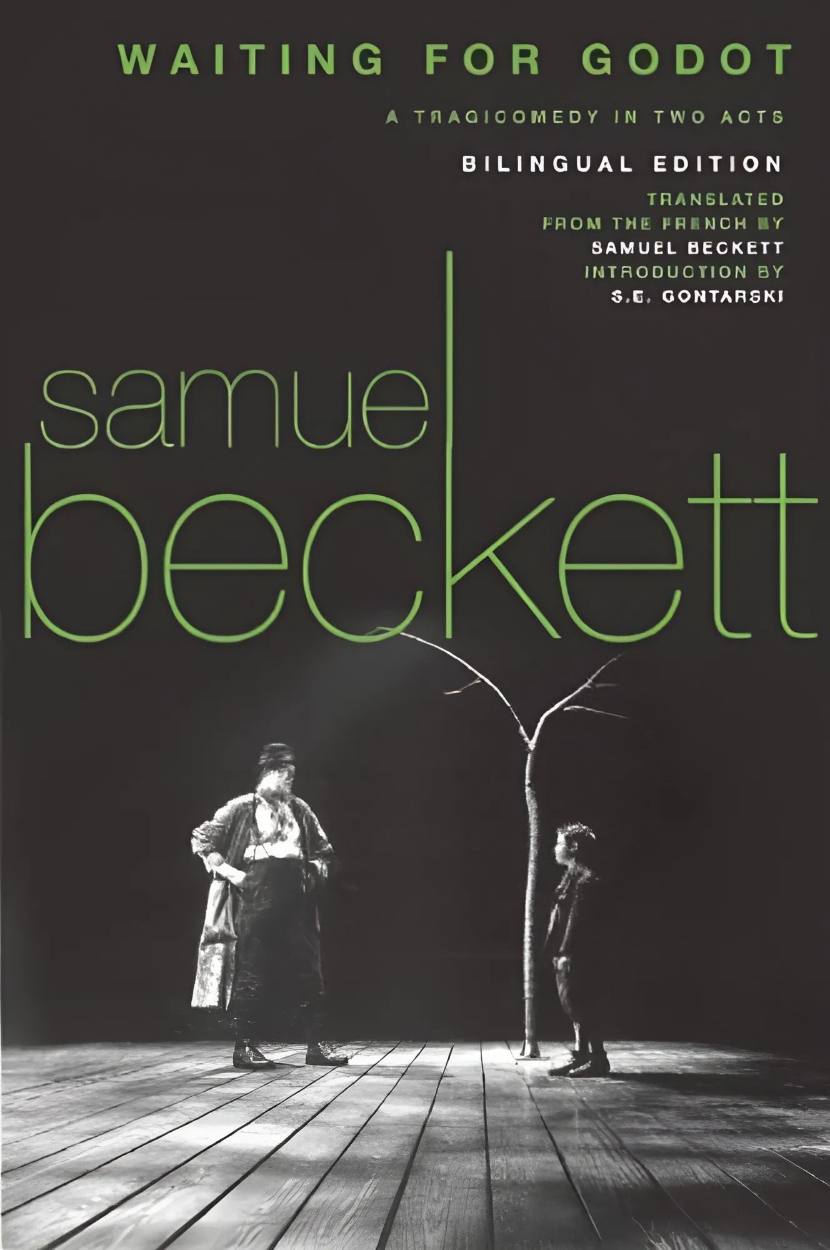

Just want to read the play?

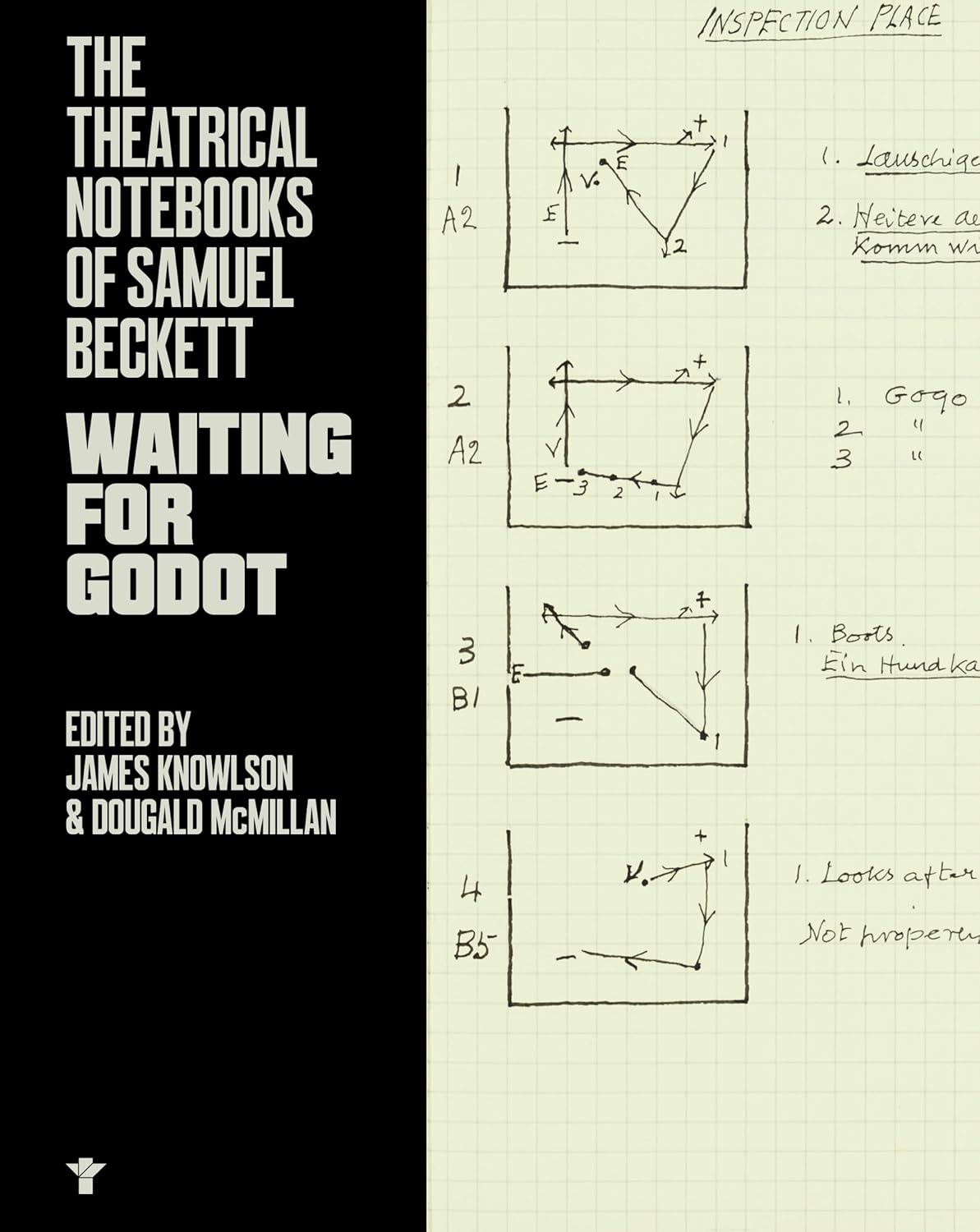

The Theatrical Notebooks of Samuel Beckett

The theatrical notebooks of Beckett are translated and annotated and offer a record of his own involvement with the staging of his texts.

Modern Theatre Guides Edition

A complete survey of the play in its cultural, theatrical, historical and political contexts.

Free version? Try the version on Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/waitingforgodot0000beck

Historical Context

Written in the aftermath of World War II, “Waiting for Godot” emerged from a Europe struggling to make sense of the Holocaust, atomic warfare, and widespread displacement. Beckett, who had been active in the French Resistance, wrote the play in French rather than his native English, perhaps to maintain emotional distance from the material. The play’s premiere in 1953 coincided with the height of Cold War tensions and existentialist philosophy’s growing influence.

Plot Overview (Or Lack Thereof)

The story, such as it is, follows Vladimir (Didi) and Estragon (Gogo), two world-weary vagrants waiting by a barren tree for someone named Godot. They fill their time with conversations, games, jokes, and contemplations of suicide. They’re visited twice by Pozzo, a wealthy man who keeps another character, Lucky, on a rope. Each act ends with a boy delivering the message that Godot won’t come today but will “surely” come tomorrow. The second act largely repeats the first, with subtle variations that suggest either hope or despair, depending on your interpretation.

Themes & Analysis

The Nature of Existence

At its core, “Waiting for Godot” explores how humans cope with existence’s fundamental uncertainty. Vladimir and Estragon’s waiting becomes a metaphor for human life itself – we all wait for something (meaning, love, success, death) while filling time with distractions and relationships.

Time and Memory

The play’s circular structure reflects how time can feel both endless and meaningless. Characters frequently forget what happened yesterday, yet remain trapped in patterns they can’t escape. As Vladimir observes, “The essential doesn’t change.”

Power Relationships

The Pozzo-Lucky dynamic offers a brutal portrait of power relationships, while Vladimir and Estragon’s co-dependent friendship shows how humans rely on each other to make existence bearable.

Revolutionary Elements

Beckett’s innovations were numerous:

- Stripped narrative to its bare essentials

- Eliminated traditional plot structure

- Combined tragedy and comedy in unprecedented ways

- Created a new theatrical language that influenced generations

- Used silence and pauses as powerful dramatic tools

Cultural Impact

“Godot” has transcended theater to become a cultural touchstone. Its influence appears in:

- Literature: Inspired writers from Harold Pinter to Tom Stoppard

- Popular culture: Referenced in everything from “The Simpsons” to “Seinfeld”

- Philosophy: Became a cornerstone of absurdist thought

- Political protest: Performed in prisons, war zones, and during civil rights movements

Staging & Performance

The play’s minimalism presents unique challenges:

- The empty stage makes actors fully exposed

- Timing of comedy and tragedy must be precise

- Physical comedy requires vaudeville-like skills

- Repetition must remain engaging

- The relationship between Vladimir and Estragon must sustain the entire show

Reading Guide

Best Translations

While Beckett translated the play himself, different editions offer various advantages:

- Grove Press edition (Beckett’s own translation) – Most authoritative

- Faber & Faber edition – Includes helpful notes

- Centenary Edition – Contains production history

Reading Tips

- Pay attention to stage directions – they’re crucial

- Notice the subtle differences between acts

- Track the changing power dynamics

- Look for vaudeville and music hall references

- Consider multiple interpretations of Godot’s identity

Contemporary Relevance

The play speaks powerfully to modern audiences:

- Social media’s endless waiting for validation

- Political deadlock and inaction

- Environmental anxiety

- Technology-induced isolation

- The search for meaning in a secular age

Fun Facts & Trivia

- Beckett insisted the title be pronounced “GOD-oh,” not “go-DOH”

- He claimed he named Godot after French slang for “boot” (godillot)

- The play was initially rejected by many theaters

- Early audiences walked out in protest

- Prisoners at San Quentin gave it one of its most enthusiastic receptions

Why It Matters

“Waiting for Godot” revolutionized theater by showing that:

- Nothing can be everything

- Absence can be presence

- Waiting can be action

- Tragedy and comedy are inseparable

- Questions are often more important than answers

Essential Quotes

“Nothing to be done.”

“We always find something, eh Didi, to give us the impression we exist?”

“They give birth astride of a grave, the light gleams an instant, then it’s night once more.”

“Was I sleeping, while the others suffered?”

Additional Resources

- “The Making of Samuel Beckett’s ‘Waiting for Godot'” by James Knowlson

- Film version with Barry McGovern and Johnny Murphy

- The Beckett International Foundation archives

- Various recorded stage productions available through Digital Theatre+

Reading “Waiting for Godot” isn’t just an exercise in theatrical history – it’s an encounter with questions that become more relevant with each passing year. In our age of perpetual waiting (for emails, updates, notifications), Beckett’s masterpiece speaks to us with renewed urgency. It reminds us that while we’re all waiting for our own Godot, the real meaning might lie in how we spend the time in between.