Tennessee Williams’ Masterpiece of Desire and Delusion

In the sweltering heat of New Orleans’ French Quarter, a fading Southern belle steps off a streetcar named “Desire,” carrying nothing but a trunk full of costume jewelry and the tattered remains of her dignity. What follows is perhaps the most searing exploration of desire, delusion, and destruction ever brought to the American stage. Tennessee Williams’ “A Streetcar Named Desire” doesn’t just depict the collision of two worlds – it shows us the violent death of one America and the raw, unflinching birth of another.

Quick Facts

- First performed: December 3, 1947, at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre, New York

- Runtime: Approximately 3 hours

- Structure: 11 scenes across 2 acts

- Awards: 1948 Pulitzer Prize for Drama, New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award

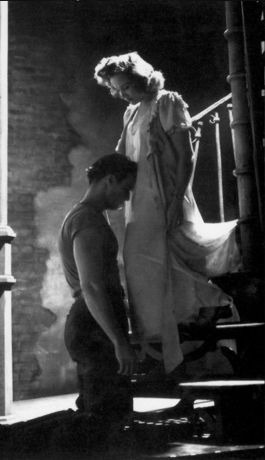

- Notable productions: Original Broadway production starring Marlon Brando and Jessica Tandy; 1951 film adaptation with Vivien Leigh

- Famous performers who’ve tackled the role of Blanche: Vivien Leigh, Jessica Tandy, Rachel Weisz, Gillian Anderson, Cate Blanchett

Just want to read the play?

Free version? Try the version on the Internet Archive: https://archive.org/details/dli.ernet.242956

Historical Context

Written in the aftermath of World War II, “Streetcar” emerged at a pivotal moment in American history. The old social order – particularly in the South – was crumbling, while a new, more brutally honest America was taking its place. The play premiered just as the American Dream was being redefined, with returning veterans like Stanley Kowalski representing a new kind of social mobility, while Blanche DuBois embodied the dying aristocracy of the Old South.

The play’s New Orleans setting is crucial – a city where the refined French Quarter borders working-class neighborhoods, where elegance and rawness coexist, and where the oppressive heat seems to strip away all pretense. Williams chose this location deliberately, making the city itself a character in the drama.

Plot Overview

Blanche DuBois, a fading Southern belle, arrives at her sister Stella’s New Orleans apartment, fleeing her troubled past in Laurel, Mississippi. She’s immediately at odds with Stella’s husband, Stanley Kowalski, a brutish but magnetic factory worker. As Blanche attempts to rebuild her life, possibly through a relationship with Stanley’s friend Mitch, her carefully constructed fantasies begin to unravel. Stanley, suspicious of Blanche’s story, uncovers her scandalous past in Laurel, including her inappropriate relationship with a student and her reputation for promiscuity. When Mitch learns the truth, he abandons his courtship of Blanche. The play culminates in Stanley’s brutal assault on Blanche, which finally shatters her already fragile psyche. In the devastating conclusion, Blanche is committed to a mental hospital, retreating fully into her illusions as she famously declares, “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers.”

Themes & Analysis

The Death of the Old South

Through Blanche, Williams presents the decay of Southern gentility. Her obsession with appearance, refinement, and the past represents a dying way of life. The loss of Belle Reve, the family plantation, serves as a metaphor for the collapse of the aristocratic South.

Desire and Sexuality

The play’s title isn’t just geographical – desire drives every major character. Stella’s sexual desire for Stanley keeps her in an abusive relationship. Blanche’s past desires led to her downfall, while her present desire for security leads to self-deception. Stanley’s desires are raw and unrestrained, representing a new, more primitive American masculinity.

Truth vs. Illusion

The central conflict between Stanley and Blanche is essentially a battle between truth and illusion. Blanche lives in a world of romantic fantasies, paper lanterns, and genteel pretense. Stanley represents harsh reality and brutal honesty. The play asks: Is there value in illusion? Is truth always better than a comforting lie?

Light and Shadow

Williams uses light symbolically throughout the play. Blanche avoids bright light, preferring the dimness of paper lanterns that hide the realities of age and time. Her final confrontation with Stanley occurs in stark light, representing the brutal exposure of truth.

Revolutionary Elements

When “Streetcar” premiered, its raw sexuality, psychological complexity, and unvarnished portrayal of domestic violence were groundbreaking. The play’s innovative use of music, lighting, and symbolic sets influenced theatrical production for decades. Williams’ poetic dialogue, combined with brutal realism, created a new theatrical language.

Cultural Impact

The play revolutionized American theater and cinema, particularly through Elia Kazan’s 1951 film adaptation. Marlon Brando’s portrayal of Stanley Kowalski invented a new style of naturalistic acting that influenced generations of performers. The play’s phrases have entered common language: “I have always depended on the kindness of strangers” and “STELLA!” are now cultural touchstones.

Reading Guide

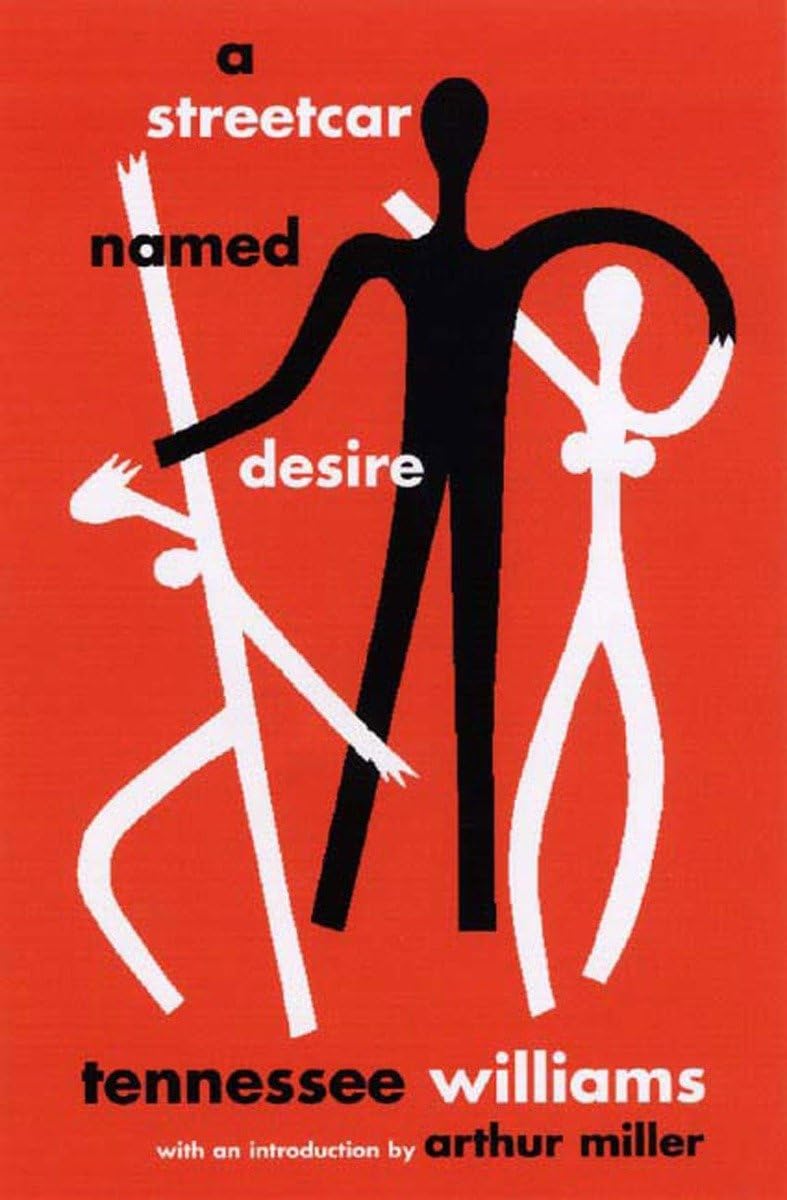

Best Editions

- New Directions Publishing (with Williams’ original stage directions)

- The Library of America edition (with scholarly notes)

- Norton Critical Edition (including critical essays)

Reading Tips

- Pay attention to Williams’ detailed stage directions – they’re practically prose poems

- Note the music and sound effects, particularly the “blue piano” that plays throughout

- Track the symbolism of light and darkness

- Watch for the streetcar metaphor: Desire leads to Cemeteries and then to Elysian Fields

Contemporary Relevance

The play’s themes remain startlingly relevant:

- The conflict between truth and necessary illusion in the age of “alternative facts”

- Class conflict and social mobility

- Sexual politics and power dynamics

- Mental health and society’s treatment of the vulnerable

- The tension between reality and self-created narrative

Fun Facts & Trivia

- The streetcar named “Desire” was a real New Orleans transit line

- Williams based Blanche partly on his own sister, Rose, who underwent a lobotomy

- The role of Stanley was originally offered to John Garfield, not Marlon Brando

- Jessica Tandy won a Tony Award for the original Broadway production, but was replaced by Vivien Leigh in the film

- The play was initially performed without its crucial rape scene, which was considered too shocking

Why It Endures

“A Streetcar Named Desire” endures because it operates on multiple levels – as a character study, as social commentary, and as pure drama. Its poetry elevates it beyond mere naturalism, while its psychological insight makes it more than just a poetic tragedy. It’s a play that speaks to both the particular moment of its creation and to eternal human struggles with desire, delusion, and dignity.

The play asks questions that still haunt us: How do we survive in a world that doesn’t match our illusions? What happens when refinement confronts brutality? How much truth can the human heart bear? In an era of alternative facts and carefully curated social media personas, Blanche’s struggle with reality feels more relevant than ever.

Whether you’re a first-time reader or returning to the text, “A Streetcar Named Desire” offers new insights with each encounter. It’s not just a play to read before you die – it’s a play that helps you understand what it means to be alive.