The Most Fascinating Anti-Heroine in Modern Drama

What drives a woman to burn the manuscript of an unborn child? To manipulate those around her with cold precision? To choose death over the mundane? Henrik Ibsen’s masterpiece “Hedda Gabler” (1891) presents us with one of theater’s most complex characters – a woman trapped between her aristocratic past and bourgeois present, between societal expectations and personal desires, between boredom and the fear of scandal.

Quick Facts

- First performed: January 31, 1891, at the Königliches Residenz-Theater in Munich

- Original language: Norwegian

- Runtime: Approximately 2.5 hours

- Structure: Four acts

- Setting: A villa in Kristiania (now Oslo), Norway

- Notable productions: 2017 National Theatre (Ruth Wilson), 2009 Broadway (Mary-Louise Parker), 1975 Broadway (Maggie Smith)

Just want to read the play?

Deborah Dawkin and Erik Skuggevik’s translation

Also contains The Wild Duck, The Lady from the Sea, and Rosmersholm.

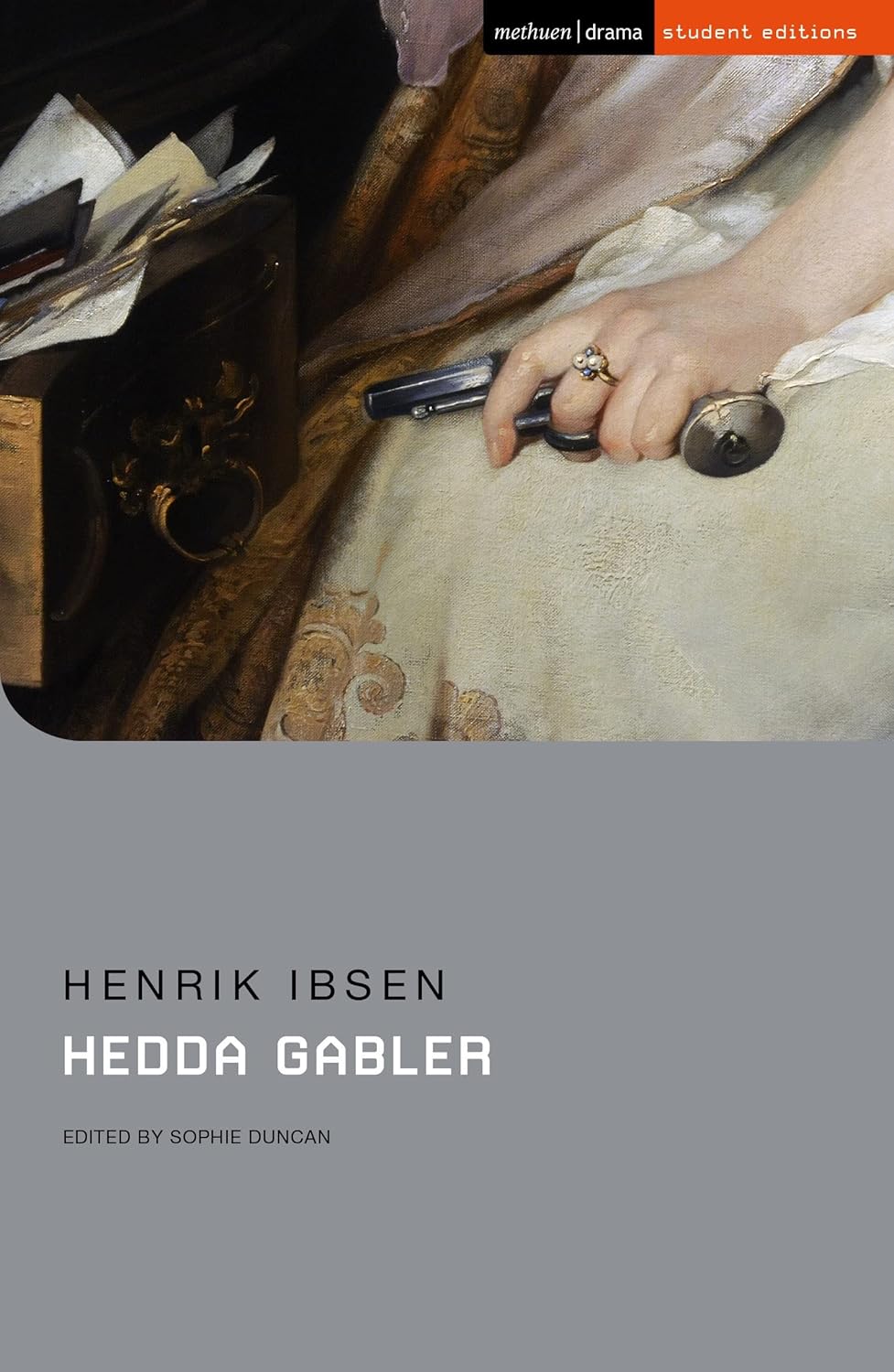

Sophie Duncan’s translation – Student Edition

Contains annotations, contextual notes and a critical essay.

BBC Henrik Ibsen film collection

Hedda Gabler, Ghosts, Little Eyolf, The Wild Duck, The Master Builder

Free version? Try the version on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/4093/4093-h/4093-h.htm

Historical Context

When Ibsen wrote “Hedda Gabler” in 1890, Europe was experiencing massive social upheaval. The women’s rights movement was gaining momentum, yet Victorian values still dominated society. Norway, though progressive for its time, remained a country where women’s options were limited to marriage and motherhood. The emerging middle class was replacing the old aristocracy, creating tension between traditional values and modern aspirations.

The play emerged during what scholars call Ibsen’s psychological realism phase, moving away from his earlier social problem plays. While “A Doll’s House” (1879) dealt explicitly with women’s rights, “Hedda Gabler” delves deeper into the psychological imprisonment of its protagonist.

Plot Overview

Hedda Gabler, daughter of General Gabler, has just returned from her honeymoon with George Tesman, an academic she married more out of convenience than love. Their peaceful if boring existence is disrupted by the arrival of Mrs. Elvsted, who brings news of Ejlert Lövborg, Tesman’s academic rival and Hedda’s former admirer. Lövborg, a reformed alcoholic, has written a groundbreaking manuscript with Mrs. Elvsted’s help.

What follows is a masterclass in manipulation as Hedda orchestrates events leading to Lövborg’s downfall, burning his manuscript (which he calls his and Mrs. Elvsted’s “child”) and providing him with a pistol for his “beautiful” death. When Judge Brack threatens to expose her role in Lövborg’s death, Hedda, refusing to be under anyone’s power, takes her own life with her father’s pistol.

Themes & Analysis

The Cage of Respectability

Hedda’s tragic flaw isn’t just her destructive nature – it’s her paralyzing fear of scandal combined with her contempt for social conventions. She’s trapped in what she calls “this middle-class life,” yet her aristocratic pride prevents her from escaping it. Her marriage to Tesman represents everything she despises: mediocrity, domesticity, and bourgeois contentment.

Power and Control

Every action Hedda takes is an attempt to exert control over her increasingly limited world. Unable to control her own destiny in a male-dominated society, she seeks power through manipulation. The pistols – her father’s legacy – represent both power and liberation, serving as Chekhov’s proverbial gun that must go off.

Beauty in Destruction

Hedda’s obsession with a “beautiful” death reveals her romantic worldview corrupted by reality. She orchestrates Lövborg’s death like a theater director, providing him with the pistol and instructing him to make it “beautiful.” When reality fails to match her aesthetic ideals (Lövborg dies in a brothel), she stages her own death with more success.

Revolutionary Elements

What made “Hedda Gabler” revolutionary was its psychological complexity. Unlike Ibsen’s previous heroines, Hedda isn’t fighting for a cause – she’s fighting against the emptiness of her existence. The play’s innovation lies in its portrait of existential boredom and its consequences.

The play’s structure is remarkable for its precision. Like a well-made watch, every scene clicks perfectly into place, building tension through seemingly casual conversations until the explosive finale.

Cultural Impact

“Hedda Gabler” has become a touchstone for feminist criticism, though Ibsen himself denied writing it as a feminist play. The character of Hedda has been interpreted as everything from a victim of patriarchal society to a proto-feminist rebel to a destructive narcissist. Each generation finds its own Hedda, reflecting contemporary attitudes toward gender, power, and society.

Reading Guide

Best Translations

- Rolf Fjelde’s translation captures the play’s psychological nuances

- Michael Meyer provides excellent cultural context

- Brian Johnston’s version emphasizes the play’s poetic elements

Reading Tips

Pay attention to:

- The symbolism of the pistols and manuscript

- References to hair and beauty

- The role of furniture and domestic space

- The unseen character of General Gabler

- The use of indirect dialogue

Contemporary Relevance

Modern audiences might recognize in Hedda the existential malaise of someone trapped in a life they never wanted. Her struggle with societal expectations resonates with contemporary discussions about women’s roles and choices. The play’s exploration of toxic relationships, manipulation, and the price of conformity remains startlingly relevant.

Discussion Questions

- Is Hedda a victim of society or a victimizer?

- What role does gender play in Hedda’s tragedy?

- How would the play be different if set in modern times?

- Is Hedda’s suicide an act of cowardice or courage?

- What is the significance of burning Lövborg’s manuscript?

Fun Facts & Trivia

- The play was originally titled “Hedda Tesman” before Ibsen changed it to emphasize Hedda’s connection to her father

- Actress Elizabeth Robins, who played Hedda in the first English production, also wrote one of the earliest feminist interpretations of the play

- The role of Hedda is often called “the female Hamlet” for its complexity and challenges

- The play was controversial upon its premiere, with one critic calling it “a repulsive tragedy”

Why This Play Endures

“Hedda Gabler” remains powerful because it resists easy interpretation. It’s a psychological thriller, a social commentary, and a character study all in one. Like its protagonist, the play maintains its fascination through ambiguity and complexity. It asks questions about freedom, responsibility, and the human capacity for destruction that still resonate today.

Whether you see Hedda as a victim, villain, or rebel, her story continues to captivate audiences and readers, proving that great drama, like great characters, never grows old – it only grows more complex with time.