The Door Slam Heard Around the World

When Nora Helmer walked out on her husband and children in the final moments of Henrik Ibsen’s “A Doll’s House,” she didn’t just exit a Norwegian home – she shattered the foundations of 19th-century theater. That famous door slam still echoes today, challenging our understanding of marriage, personal identity, and the price of freedom.

Quick Facts

- First performed: December 21, 1879, at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, Denmark

- Original title: Et dukkehjem (Norwegian)

- Runtime: Approximately 2 hours and 15 minutes

- Structure: Three acts

- Initial reception: Controversial, banned in Britain until 1884

- Notable adaptations: Patrick Marber’s 2016 “Nora,” Carrie Cracknell’s 2012 Young Vic production, Ivo van Hove’s 2022 radical reimagining

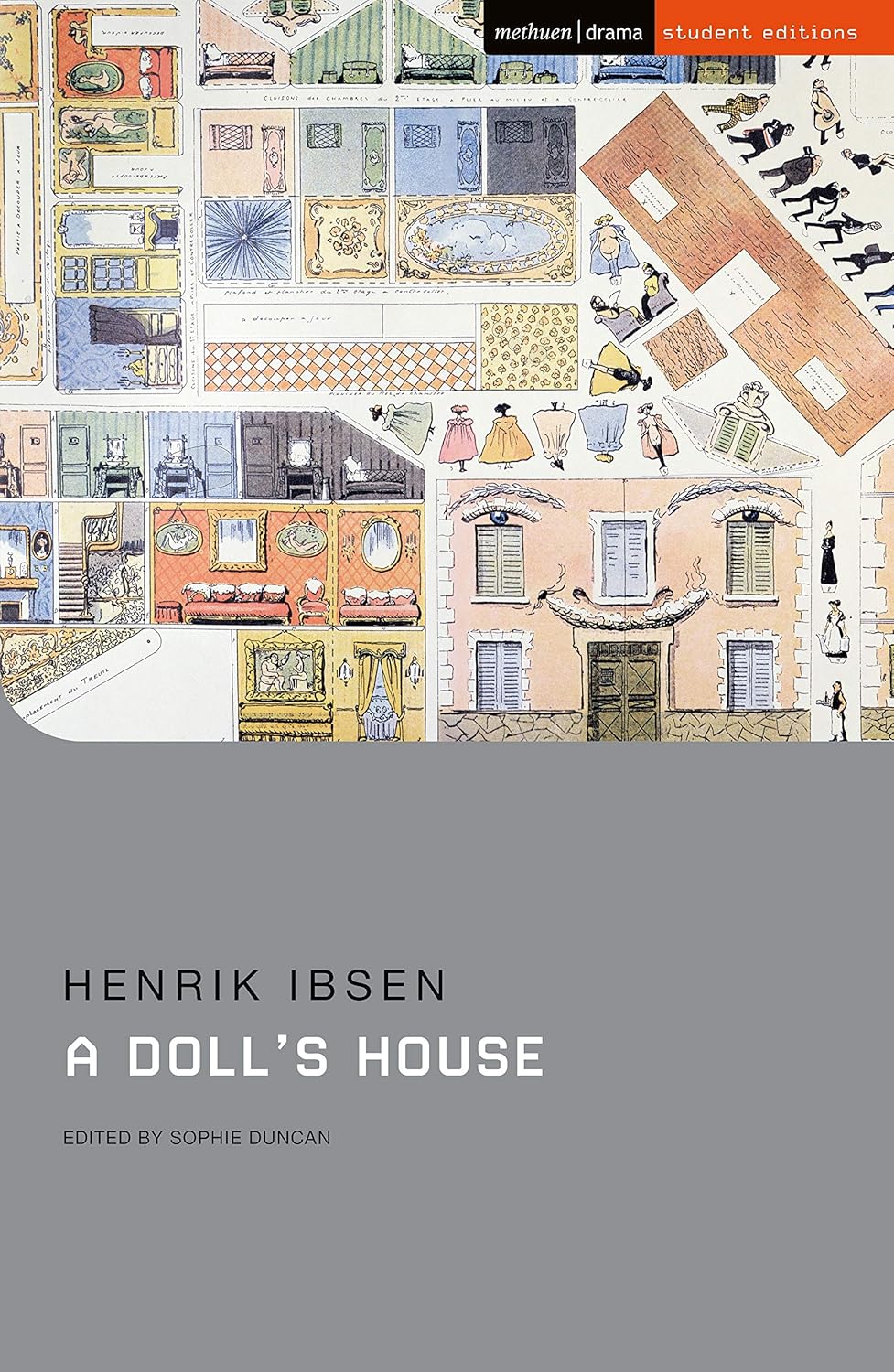

Just want to read the play?

Michael Meyer’s translation – student edition

Contains notes by editor Sophie Duncan, including a critical essay on the play.

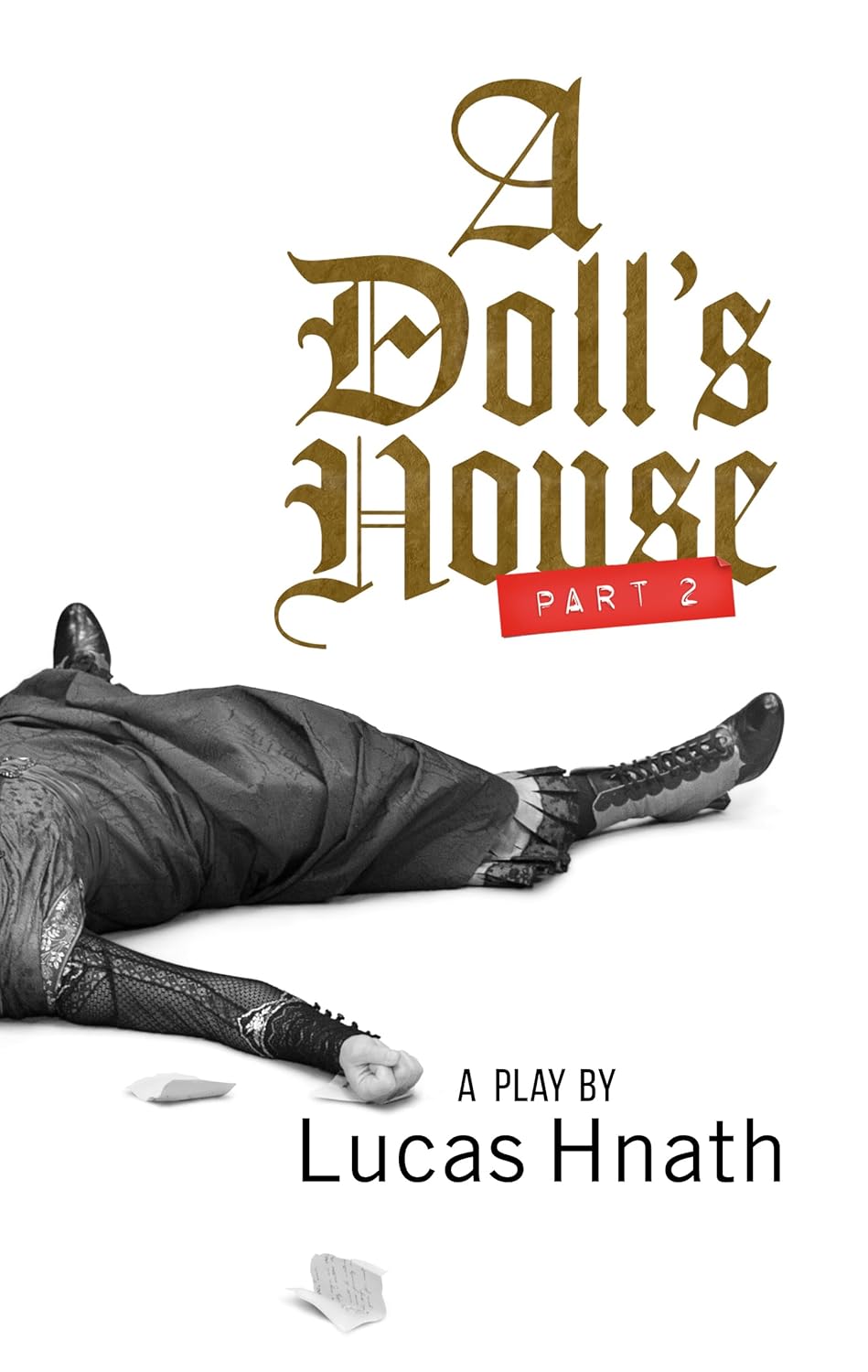

A Doll’s House Part 2 by Lucas Hnath

This much praised “sequel” to Ibsen’s classic, is well worth reading in tandem with the original.

Free version? Try the version on Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2542/2542-h/2542-h.htm

Historical Context

In 1879, married women couldn’t take out loans, own property, or even have custody of their children in most European countries. Ibsen wrote “A Doll’s House” against this backdrop of suffocating gender inequality, during a period when the first waves of feminism were beginning to ripple through society. The play emerged during the Modern Breakthrough, a literary movement that rejected Romanticism in favor of realistic problems and taboo subjects.

The play’s premiere caused an uproar so severe that some dinner party hosts included “No discussion of A Doll’s House” on their invitations. Actresses initially refused to play Nora’s final scene, and Ibsen was forced to write an alternate ending (which he later called “a barbaric outrage”) for German productions.

Plot Overview

Nora Helmer appears to live a picture-perfect life with her husband Torvald and their three children. But beneath the surface lurks a secret: years ago, Nora forged her father’s signature to secure a loan that saved Torvald’s life. She’s been secretly repaying it ever since, believing she acted out of love.

When the loan’s existence threatens to become public through the machinations of Krogstad, a desperate employee at Torvald’s bank, Nora’s carefully constructed world begins to crumble. Her husband’s reaction to the truth – prioritizing his reputation over her sacrifice – forces Nora to confront the infantilizing nature of their marriage and her own stunted development as a human being.

Themes & Analysis

The Gilded Cage

Ibsen masterfully constructs the Helmer household as a beautiful prison, with Torvald as its unwitting warden. The pet names he uses for Nora – “little skylark,” “squirrel,” “songbird” – reveal his infantilizing view of his wife. The Christmas tree, usually a symbol of joy and family, becomes a mirror of Nora herself: decorated and displayed for others’ pleasure.

Economics of Marriage

Money drives the plot, but it’s really about the economics of human relationships. Every character is caught in some form of debt – financial or emotional. Nora’s secret loan represents both her power to act independently and her bondage to patriarchal systems.

Identity and Self-Discovery

The play’s genius lies in how Nora’s awakening feels both inevitable and shocking. Her realization that she’s been “a doll-wife” in her father’s and husband’s houses lands with devastating clarity. Her famous line “Before all else, I’m a human being” was revolutionary in 1879 and remains powerful today.

Revolutionary Elements

Ibsen’s innovation wasn’t just in his subject matter – he revolutionized dramatic structure. The play follows what would become known as “retrospective exposition,” where past events gradually come to light through natural conversation rather than artificial monologues. This technique creates both psychological realism and detective-story suspense.

The play also subverts the “well-made play” formula popular at the time. Instead of a neat resolution, we get an ending that raises more questions than it answers.

Cultural Impact

“A Doll’s House” has influenced everything from feminist theory to modern sitcoms. Its DNA can be found in works as diverse as Kate Chopin’s “The Awakening” and “Revolutionary Road.” The play has been adapted countless times, including fascinating cultural translations like Aisha, a 2003 Bollywood version set in modern Mumbai.

Reading Guide

Best Translations

- Michael Meyer’s translation captures the play’s domestic immediacy

- Rolf Fjelde offers the most accurate Norwegian nuances

- Simon Stephens’s recent adaptation (2012) brings fresh energy while maintaining the period setting

Reading Tips

- Pay attention to the symbolism of doors opening and closing

- Notice how money exchanges hands throughout the play

- Track the evolution of Nora’s language from childish to mature

- Watch how Ibsen uses the Christmas tree as a barometer of Nora’s state of mind

Contemporary Relevance

While women’s rights have advanced significantly since 1879, the play’s core questions remain startlingly relevant:

- How much of ourselves do we sacrifice to meet others’ expectations?

- Can a relationship survive complete honesty?

- What do we owe ourselves versus what we owe our families?

- How do economic power and personal autonomy intersect?

Recent productions have found new resonance in the age of #MeToo and conversations about emotional labor in relationships.

Fun Facts & Trivia

- Ibsen based the character of Nora on Laura Kieler, a friend who had gone through a similar crisis

- The play was partly inspired by the true story of Martha Nilsson, who forged checks to save her dying husband

- Early productions often changed the ending to have Nora return to her children

- The play was banned in Britain until 1884, and private productions were staged in men’s clubs

- The role of Nora has been called “the female Hamlet” for its complexity and demanding nature

Conclusion

“A Doll’s House” earns its place among the must-read plays not just for its historical importance, but for its continued ability to provoke and challenge. It asks questions that each generation must answer anew about identity, love, and the price of personal freedom. The door that Nora opens leads not just to her own liberation, but to an ongoing conversation about human rights, personal autonomy, and the nature of marriage that continues to this day.

When you read “A Doll’s House,” you’re not just reading a feminist landmark or a masterpiece of realist drama – you’re encountering a work that helps us understand what it means to be human, to be free, and to face the consequences of that freedom. In an age of carefully curated social media personas and increasing concerns about authenticity, Nora’s journey from decorative doll to fully realized human being feels more relevant than ever.

Additional Resources

- “The Making of Modern Drama” by Richard Gilman

- “Ibsen and the Birth of Modernism” by Toril Moi

- The Young Vic’s 2012 production (available on Digital Theatre)

- BBC Radio 3’s In Our Time episode on Ibsen

- The British Library’s collection of original reviews and responses